When the Divine Met the Dangerous: Paint, Power and Poison in Interiors

HABITUS ELEMENTUS: Non-toxic Paint [Part 2 - From Instinct to Sacred]

In our last HABITUS post, we covered the origin story of prehistoric paint, its original purpose and discovery, how paint became toxic to glorify pharaohs, and how paint, at its core, is a human instinct. (Prehistoric and Egyptian Paint)

We learned that our current homes, from layout to aesthetic, have more in common with ancient structures and ways of living than we really realize.

PSA: Cabinet update - I haven’t had any time to work on it, but plan to over the next two weeks.

With the headlines in the news about certain medications causing harm to human health and the public reaction, it has once again turned my attention to my work with HABITUS.

What if health isn’t just something we ingest or don’t? What if our environments cause harm without us even knowing it? Even if an expert says it is ok.

I feel like there is a war on truth in every aspect of health and well-being currently.

We left off telling the story of the Egyptian tomb painters and learned about some deadly ingredients. This week, we pick up with more sacred spaces.

Sacred Color

You awaken in your small stone house near the Tiber River to the smell of smoke and bread.

It is just another day in Rome in 1510.

You rise before the sun, pull on a scratchy and rough wool tunic and and slide your feet into sandals.

As you place your tunic over your head, some of the lead white powder creates a cloud in your room.

You break your fast with some simple day-old bread dipped in olive oil and a small piece of cheese from the market down the via or street.

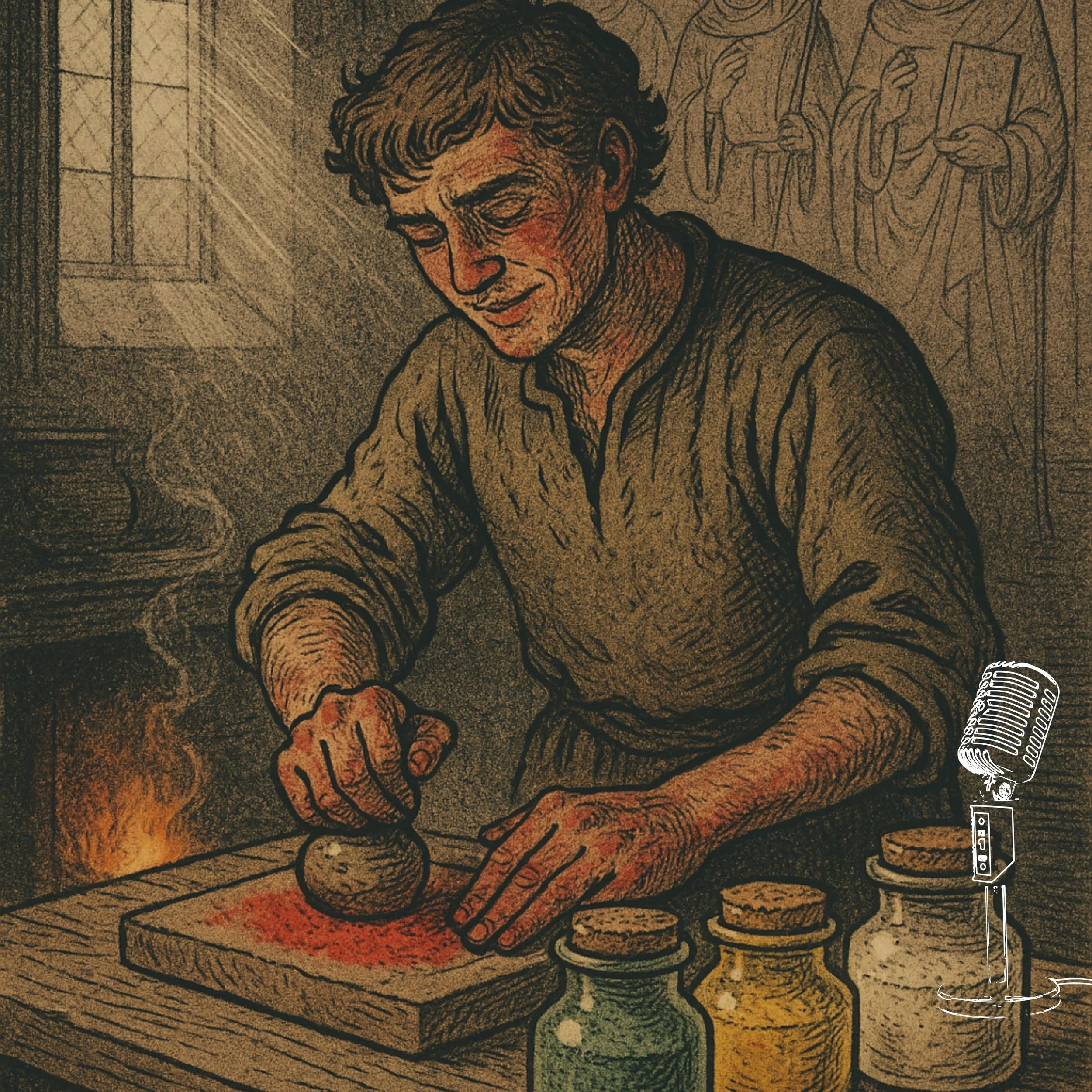

As you dip your bread, you look down at your green-stained fingers and hands. For years, you were only an apprentice to the craftsmen working on the sacred structures in Rome.

You spent most of the time in your apprenticeship and childhood grinding pigments like vermillion and orpiment.

You worked until your hands were blistered and the dust filled your lungs with a heavy feeling that never seems to dissipate.

You walk down the stone via toward Vatican City, passing merchants as they awaken for today’s trades and pilgrims from their shelters.

The city is alive, but your world is the scaffolding, the brushes, the colors that glorify God.

When you arrive, you are greeted with the sight of scaffolding as you enter the Sistine Chapel, high above the cold marble floor.

You tilt your head back and let your eyes adjust, and the artwork on the ceiling comes into focus.

The morning light filters through small windows. Left from yesterday’s work, you squint at the colorful pigments of lead white, verdigris, and cinnabar.

The colors are a vivid contrast to the incomplete plaster and stone on the ceiling. You begin to mix the pigments with water and lime plaster.

The smell and powder sting your eyes as you begin your work for today.

You are completely awakened by Michelangelo’s voice as he enters the chapel and loudly demands more blue for heaven, and more red for the details on the robes of the saints.

You immediately begin your task of creating the paint for this sacred space, but you notice that your head begins to ache and your stomach hurts.

Still, you mix on, knowing you are consecrating God’s Glory.

Color and Theology

Most painters were trained in guild workshops and were responsible for grinding pigments before being allowed to touch a brush.

The process of grinding, mixing, and heating pigments was constant and often done without any protection.

The painters of sacred spaces in Cathedrals and Chapels believed their work was a holy sacrifice for divine art.

Cathedrals and Chapels became canvases for divine storytelling.

The paintings in these spaces were designed with the illiterate in mind.

From about the 5th to the 15th century, the overwhelming majority of people could not read Latin, which was the language of the church.

Paintings in these sacred spaces became a visual bible or the bible for the poor. They illustrated stories of Creation, lives of saints, the Passion of Christ, and visions of heaven and hell.

Paint was now no longer just for survival and decoration, but a theological tool. The art is didactic - it taught moral lessons and reinforced Church doctrine visually.

Pigments and Poisons of God’s Glory

Holy White

(Basic Lead Carbonate) The dominant white pigment used for over a millennium was lead white. This pigment was used as early as Ancient Greece and Rome.

Its preparation was described by Pliny the Elder. Strips of metallic lead were placed in clay pots and were partly filled with vinegar and then buried in stacks of manure.

The heat and carbon dioxide from the manure and the vinegar fumes corroded the lead over several weeks and formed a crust, which was scraped and ground into pigment.

This mixture was extremely toxic and caused the condition called “painters’ colic” or symptoms such as cramps, tremors, and neurological decline.

Sacred Blood Red

(Mercury Sulfide) The vermillion pigment is derived from cinnabar and was the most commonly used red pigment.

The Latin name vermiculus translates as “little worm,” because an early red dye came from crushed insects.

In China, artisans developed a technique of heating the pigment to further refine and brighten the color.

ermillion was used to create brilliant reds, and the color was associated with power and sacred blood.

Grinding cinnabar into a fine pigment released mercury dust, causing symptoms such as tremors, memory loss, and mood disorders.

Virgin Green

(Copper Acetate) The hopeful, bright green color is created from exposing copper plates to vinegar fumes or burying copper in manure.

Over weeks, the copper plate corroded and created a green crust, which was scraped off to use to create a jewel-toned green.

The original color in Old French was called vert-de-Grèce or green of Greece because it was first traded through Greek merchants.

Grinding the dust released fumes that irritated eyes, lungs, and skin. Chronic exposure leads to symptoms such as headaches, vomiting, and “copper colic.”

Eternal Light Yellow and Gold

(Arsenic Sulfide) In the 15th century, Cennino Cennini wrote a book called the Book of the Artisan working with apprentices, about the sacred yellow gold paint, stating, “Beware of handling orpiment, for it is poison.”

The most dazzling and most dangerous pigment in history, orpiment comes from the Latin auripigmentum, translating as “gold pigment.”

It was used by Egyptians, Persians, and Romans. Found naturally near volcanic vents, hot springs, and was a byproduct of mining.

The crystals were collected and then ground into powder. This gold-yellow pigment rivaled gold leaf, and its richness remained unmatched until the 19th century. Handling orpiment with bare skin could cause rashes, sores, and systemic poisoning.

Symptoms included acute nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. More severe symptoms included skin lesions, nerve damage, liver and kidney injury, and cancers.

From Innate to Sacred

By the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, paint was no longer confined to tombs; it was sacred, symbolic, and necessary for cultural identity.

Like the Egyptians before them, (read their story here), European artisans sacrificed their health for the holy purpose of bringing biblical stories to the masses.

These pigments and paints now fill public chapels and cathedrals, exposing not only the artisans who made the didactic depictions, but the worshippers who knelt beneath their glory.

Paint Innovation

For centuries, toxic color was the hidden burden of artisans. Join me next time in Part 4 as we step into the Industrial Revolution, where paint innovation changed everything.

The pigments once reserved for kings and saints were now churned out by factories and brushed across nurseries, parlors, and storefronts.

What had been the danger of a painter’s hand became the shared poison of entire households.

The Industrial Revolution promised brighter, cheaper, more accessible color, but in doing so, it carried toxic paints into every corner of daily life.

Subscribe to follow along on paint’s historical journey and modern paint’s story.